Video Playback On The Web: Video Delivery Best Practices (Part 2)

Video Playback On The Web: Video Delivery Best Practices (Part 2)

Doug Sillars

In my previous post, I examined video trends on the web today, using data from the HTTP Archive. I found that many websites serve the same video content on mobile and desktop, and that many video streams are being delivered at bitrates that are too high to playback on 3G speed connections. We also discovered that may websites automatically download video to mobile devices — damaging customer’s data plans, battery life, for videos that might not ever be played.

TL;DR: In this post, we look at techniques to optimize the speed and delivery of video to your customers, and provide a list of 9 best practices to help you deliver your video assets.

Video Playback Metrics

There are 3 principal video playback metrics in use today:

- Video Startup Time

- Video Stalling

- Video Quality

Since video files are large, optimizing the video to be as small as possible will lead to faster video delivery, speeding up video start, lowering the number of stalls, and minimizing the effect of the quality of the video delivered. Of course, we need to balance startup speed and stalling with the third metric of quality (and higher quality videos generally use more data).

Video Startup

When a user presses play on a video, they expect to be able to watch the video quickly. According to Conviva (a leader in video metric analysis), in Q1 of 2018, 14% of videos never started playing (that’s 2.4 Billion video plays) after the user pressed play.

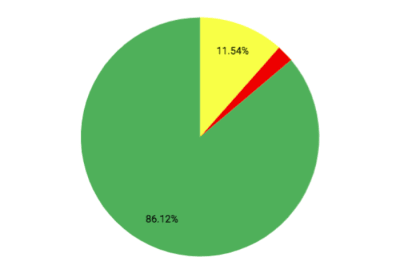

2.3% of videos (400M video requests) failed to play after the user pressed the play button. 11.54% (2B plays) were abandoned by the user after pressing play. Let’s try to break down what might be causing these issues.

Video Playback Failure

Video playback failure accounted for 2.3% of all video plays. What could lead to this? In the HTTP Archive data, we see 0.3% of all video requests resulting in a 4xx or 5xx HTTP response — so some percentage fail to bad URLs or server misconfigurations. Another potential issue (that is not observed in the HTTP Archive data) are videos that are blocked by Geolocation (blocked based on the location of the viewer and the licensing of the provider to display the video in that locale).

Video Playback Abandonment

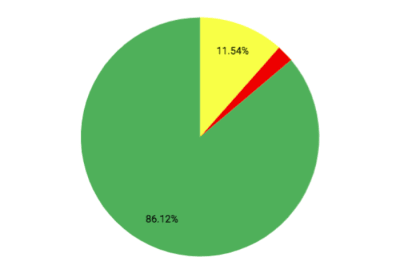

The Conviva report states that 11.5% of all video plays would play, but that the customer abandoned the playback before the video started playing. The issue here is that the video is not being delivered to the customer fast enough, and they give up. There are many studies on the mobile web where long delays cause abandonment of web pages, and it appears that the same effect occurs with video playback as well.

Research from Akamai shows that viewers will wait for 2 seconds, but for each subsequent second, 5.8% of viewers abandon the video.

So what leads to video playback issues? In general, larger files take longer to download, so will delay playback. Let’s look at a few ways that one can speed up the playback of videos. To reduce the number of videos abandoned at startup, we should ‘slim’ down these files as best as possible, so they download (and begin playback) quickly.

MP4: Video Preload

To ensure fast playback on the web, one option is to preload the video onto the device in advance. That way, when your customer clicks ‘play’ the video is already downloaded, and playback will be fast. HTML offers a preload attribute with 3 possible options: auto, metadata and none.

preload = auto

When your video is delivered with preload="auto", the browser downloads the entire video file and stores it locally. This permits a large performance improvement for video startup, since the video is available locally on the device, and no network interference will slow the startup.

However, preload="auto" should only be used if there is a high probability that the video will be viewed. If the video is simply resident on your webpage, and it is downloaded each time, this will add a large data penalty to your mobile users, as well as increase your server/CDN costs for delivering the entire video to all of your users.

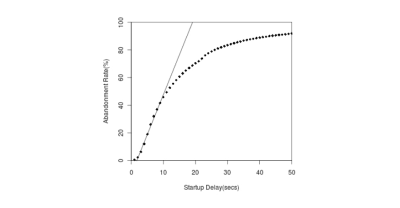

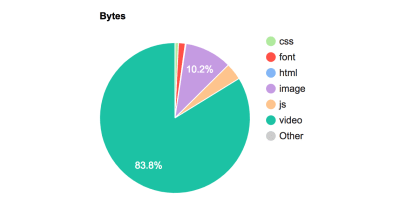

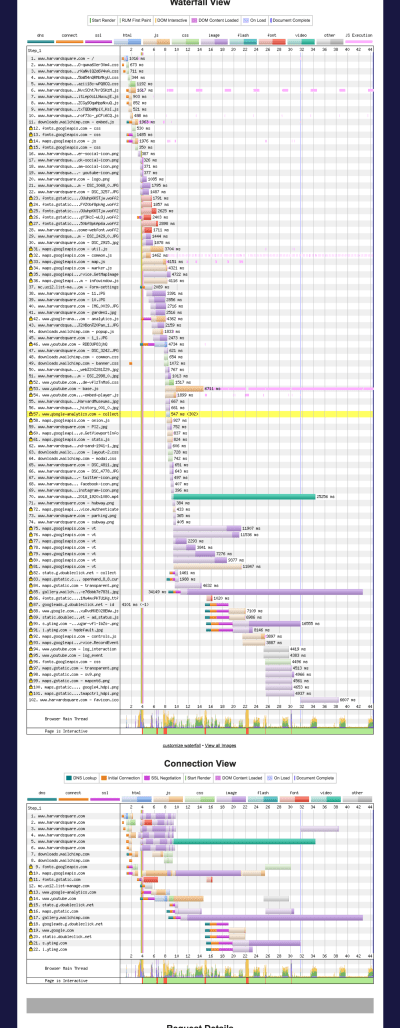

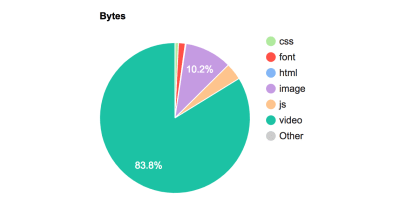

This website has a section entitled “Video Gallery” with several videos. Each video in this section has preload set to auto, and we can visualize their download in the WebPageTest waterfall as green horizontal lines:

There is a section called “Video Gallery”, and the files for this small section of the website account for 14.6M (83%) of the page download. The odds that one (of many) videos will be played is probably pretty low, and so utilizing preload="auto" only generates a lot of data traffic for the site.

In this case, it is unlikely that even one of these videos will be viewed, yet all of them are downloaded completely, adding 14.8MB of content to the mobile site (83% of the content on the page). For videos that are have a high probability of playback (perhaps >90% of page views result in video play) — preloading the entire video is a very good idea. But for videos that are unlikely to be played, preload="auto" will only cause extra tonnage of content through your servers and to your customer’s mobile (and desktop) devices.

preload="metadata"

When the preload="metadata" attribute is used, an initial segment of the video is downloaded. This allows the player to know the size of the video window, and to perhaps have a second or 2 of video downloaded for immediate playback. The browser simply makes a 206 (partial request) of the video content. By storing a small bit of video data on the device, video startup time is decreased, without a large impact to the amount of data transferred.

On Chrome, metadata is the default choice if no attribute is chosen.

Note: This can still lead to a large amount of video to be downloaded, if the video is large.

For example, on a mobile website with a video set at preload="metadata", we see just one request for video:

And the request is a partial download, but it still results in 2.7 MB of video to be downloaded because the full video is 1080p, 150s long and 97 MB (we’ll talk about optimizing video size in the next sections).

So, I would recommend that preload="metadata" still only be used when there is a fairly high probability that the video will be viewed by your users, or if the video is small.

preload="none"

The most economical download option for videos, as no video files are downloaded when the page is loaded. This will potentially add a delay in playback, but will result in faster initial page load For sites with many videos on a single page, it may make sense to add a poster to the video window, and not download any of the video until it is expressly requested by the end user. All YouTube videos that are embedded on websites never download any video content until the play button is pressed, essentially behaving as if preload="none".

Preload Best Practice: Only use preload="auto" if there is a high probability that the video will be watched. In general, the use of preload="metadata" provides a good balance in data usage vs. startup time, but should be monitored for excessive data usage.

MP4 Video Playback Tips

Now that the video has started, how can we ensure that the video playback can be optimized to not stall and continue playing. Again, the trick is to make sure the video is as small as possible.

Let’s look at some tricks to optimize the size of video downloads. There are several dimensions of video that can be optimized to reduce the size of the video:

Audio

Video files are split into different “streams” — the most common being the video stream. The second most common stream is the audio track that syncs to the video. In some video playback applications, the audio stream is delivered separately; this allows for different languages to be delivered in s seamless manner.

If your video is played back in a silent manner (like a looping GIF, or a background video), removing the audio stream from the video is a quick and easy way to reduce the file size. In one example of a background video, the full file was 5.3 MB, but the audio track (which is never heard) was nearly 300 KB (5% of the file) By simple eliminating the audio, the file will be delivered quickly without wasting bytes.

42% of the MP4 files found on the HTTP Archive have no audio stream.

Best Practice: Remove the audio tracks from videos that are played silently.

Video Encoding

When encoding a video, there are options to reduce the video quality (number of pixels per frame, or the frames per second). Reducing a high-quality video to be suitable for the web is easy to do, and generally does not affect the quality delivered to your end users. This article is not long enough for an in depth discussion of all the various compression techniques available for video. In x264 and x265 encoders, there is a term called the Constant Rate Factor (CRF). Using a CRF of 23-28 will generally give a good compression/quality trade off, and is a great first start into the realm of video compression

Video Size

Video size can be affected by many dimensions: length, width, and height (you could probably include audio here as well).

Video Duration

The length of the video is generally not a feature that a web developer can adjust. If the video is going to playback for three minutes, it is going to playback for three minutes. In cases in which the video is exceptionally long, tools like preload="none" or streaming the video can allow for a smaller amount of data to be downloaded initially to reduce page load time.

Video Dimensions

18% of all video found in the HTTP Archive is identical on mobile and desktop. Those who have worked with responsive web design know how optimizing images for different viewports can drastically reduce load times since the size of the images is much smaller for smaller screens.

The same holds for video. A website with a 30 MB 2560×1226 background video will have a hard time downloading the video on mobile (probably on desktop, too!). Resizing the video drastically decreases the files size, and might even allow for three or four different background videos to be served:

| Width | Video (MB) |

|---|---|

| 1226 | 30 |

| 1080 | 8.1 |

| 720 | 43 |

| 608 | 3.3 |

| 405 | 1.76 |

Now, unfortunately, browsers do not support media queries for video in HTML, meaning that this just does not work:

<video preload="auto" autoplay muted controls source sizes="(max-width:1400px 100vw, 1400px" srcset="small.mp4 200w, medium.mp4 800w, large.mp4 1400w" src="large.mp4" </video> Therefore, we’ll need to create a small JS wrapper to deliver the videos we want to different screen sizes. But before we go there…

Downloading Video, But Hiding It From View

Another throwback to the early responsive web is to download full-size images, but to hide them on mobile devices. Your customers get all the delay for downloading the large images (and hit to mobile data plan, and extra battery drain, etc.), and none of the benefit of actually seeing the image. This occurs quite frequently with video on mobile. So, as we write our script, we can ensure that smaller screens never request the video that will not appear in the first place.

Retina Quality Videos

You may have different videos for different device screen densities. This can lead to added time to download the videos to your mobile customers. You may wish to prevent retina videos on smaller screen devices, or on devices with a limited network bandwidth, falling to back to standard quality videos for these devices. Tools like the Network Information API can provide you with the network throughput, and help you decide which video quality you’d like to serve to your customer.

Downloading Different Video Types Based On Device Size And Network Quality

We’ve just covered a few ways to optimize the delivery of movies to smaller screens, and also noted the inability of the video tag to choose between video types, so here is a quick JS snippet that will use the screen width to:

- Not deliver video on screens below 500px;

- Deliver small videos for screens 500-1400;

- Deliver a larger sized video to all other devices.

<html><body> <div id="video"> </div> <div id="text"></div> <script> //get screen width and pixel ratio var width = screen.width; var dpr = window.devicePixelRatio; //initialise 2 videos — //“small” is 960 pixels wide (2.6 MB), large is 1920 pixels wide (10 MB) var smallVideo="http://res.cloudinary.com/dougsillars/video/upload/w_960/v1534228645/30s4kbbb_oblsgc.mp4"; var bigVideo = "http://res.cloudinary.com/dougsillars/video/upload/w_1920/v1534228645/30s4kbbb_oblsgc.mp4"; //TODO add logic on adding retina videos if (width<500){ console.log("this is a very small screen, no video will be requested"); } else if (width< 1400){ console.log("let’s call this mobile sized"); var videoTag = "<video preload="auto" width="100%" autoplay muted controls src="" +smallVideo +""/>"; console.log(videoTag); document.getElementById('video').innerHTML = videoTag; document.getElementById('text').innerHTML = "This is a small video."; } else{ var videoTag = "<video preload="auto" width="100%" autoplay muted controls src="" +bigVideo +""/>"; document.getElementById('video').innerHTML = videoTag; document.getElementById('text').innerHTML = "This is a big video."; } </script> </html></body> This script divides user’s screens into three options:

- Under 500 pixels, no video is shown.

- Between 500 and 1400, we have a smaller video.

- For larger than 1400 pixel wide screens, we have a larger video.

Our page has a responsive video with two different sizes: one for mobile, and another for desktop-sized screens. Mobile users get great video quality, but the file is only 2.6 MB, compared to the 10MB video for desktop.

Animated GIFs

Animated GIFs are big files. While both aGIFs and video files compress the data through width and height dimensions, only video files have compression (on the often larger) time axis. aGIFs are essentially “flipping through” static GIF images quickly. This lack of compression adds a significant amount of data. Thankfully, it is possible to replace aGIFs with a looping video, potentially saving MBs of data for each request.

<video loop autoplay muted src="pseudoGif.mp4"> In Safari, there is an even fancier approach: You can place a looping mp4 in the picture tag, like so:

<picture> <source type="video/mp4" loop autoplay srcset="loopingmp4.mp4"> <source type="image/webp" srcset="animated.webp"> <src="animated.gif"> </picture> In this case, Safari will play the animated GIF, while Chrome (and other browsers that support WebP) will play the animated WebP, with a fallback to the animated GIF. You can read more about this approach in Colin Bendell’s great post.

Third-Party Videos

One of the easiest ways to add video to your website is to simply copy/paste the code from a video sharing service and put it on your site. However, just like adding any third party to your site, you need to be vigilant about what kind of content is added to your page, and how that will affect page load. Many of these “simply paste this into your HTML” widgets add 100s of KB of JavaScript. Others will download the entire movie (think preload="auto"), and some will do both.

Third-Party Video Best Practice: Trust but verify. Examine how much content is added, and how much it affects your page load time. Also, the behavior might change, so track with your analytics regularly.

Streaming Startup

When a video stream is requested, the server supplies a manifest file to the player, listing every available stream (with dimensions and bitrate information). In HLS streaming, the player generally chooses the first stream in the list to begin playback. Therefore, the stream positioned first in the manifest file should be optimized for video startup on both mobile and desktop (or perhaps alternative manifest files should be delivered to mobile vs. desktop).

In most cases, the startup is optimized by using a lower quality stream to begin playback. Once the player downloads a few segments, it has a better idea of available throughput and can select a higher quality stream for later segments. As a user, you have likely seen this — where the first few seconds of a video looks very pixelated, but a few seconds into playback the video sharpens.

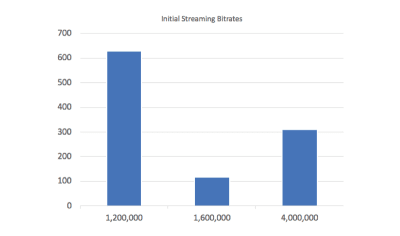

In examining 1,065 manifest files delivered to mobile devices from the HTTP Archive, we find that 59% of videos have an initial bitrate under 1.2 MBPS — and are likely to start streaming without any much delay at 1.6 MBPS 3G data rates. 11% use a bitrate between 1.2 and 1.6 MBPS — which may slow the startup on 3G, and 30% have a bitrate above 1.6 MBPS — and are unable to playback at this bitrate on a 3G connection. Based on this data, it appears that ~41% of all videos will not be able to sustain the initial bitrate on mobile — adding to startup delay, and possibly increased number of stalls during playback.

Streaming Startup Best Practice: Ensure your initial bitrate in the manifest file is one that will work for most of your customers. If the player has to change streams during startup, playback will be delayed and you will lose video views.

So, what happens when the video’s bitrate is near (or above) the available throughput? After a few seconds of download without a completed video segment ready for playback, the player stops the download and chooses a lower quality bitrate video, and begins the process again. The action of downloading a video segment and then abandoning leads to additional startup delay, which will lead to video abandonment.

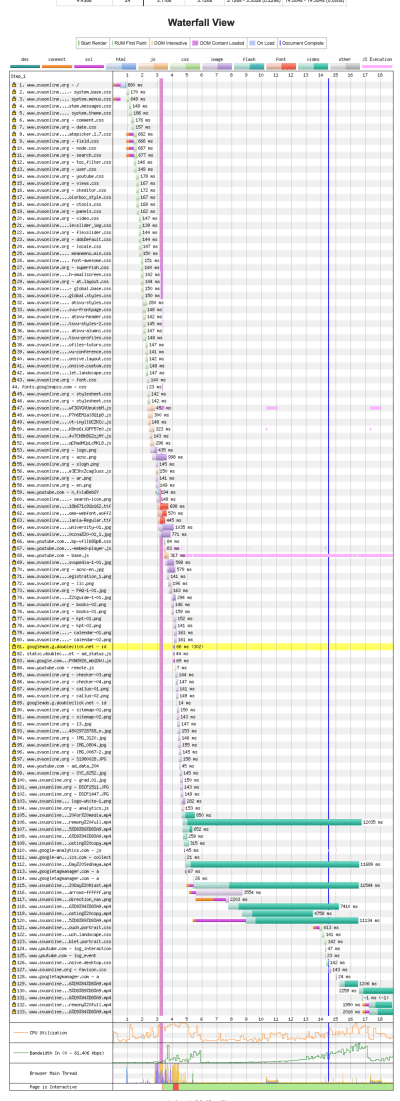

We can visualize this by building video manifests with different initial bitrates. We test 3 different scenarios: starting with the lowest (215 KBPS), middle (600 KBPS), and highest bitrate (2.6 MBPS).

When beginning with the lowest quality video, playback begins at 11s. After a few seconds, the player begins requesting a higher quality stream, and the picture sharpens.

When starting with the highest bitrate (testing on a 3G connection at 1.6 MBPS), the player quickly realizes that playback cannot occur, and switches to the lowest bitrate video (215 KBPS). The video starts playing at 17s. There is a 6-second delay, and the video quality is the same low quality delivered to in the first test.

Using the middle-quality video allows for a bit of a tradeoff, the video begins playing at 13s (2 seconds slower), but is high quality from the start -and there is no jump from pixelated to higher quality video.

Best Practice for Video Startup: For fastest playback, start with the lowest quality stream. For longer videos, you might consider using a ‘middle quality’ stream at start to deliver sharp video at startup (with a slightly longer delay).

WebPageTest results: Initial video stream is low, middle and high (from top to bottom). The video starts the fastest with the lowest quality video. It is important to note that the high quality start video at 17s is the same quality as the low quality start at 11s.

Streaming: Continuing Playback

When the video player can determine the optimal video stream for playback and the stream is lower than the available network speed, the video will playback with no issues. There are tricks that can help ensure that the video will deliver in an optimal manner. If we examine the following manifest entry:

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=912912,PROGRAM-ID=1,CODECS="avc1.42c01e,mp4a.40.2",RESOLUTION=640x360,SUBTITLES="subs" video/600k.m3u8 The information line reports that this stream has a 913 KBPS bitrate, and 640×360 resolution. If we look at the URL that this line points to, we see that it references a 600k video. Examining the video files shows that the video is 600 KBPS, and the manifest is overstating the bitrate.

Overstating The Video Bitrate

- PRO

Overstating the bitrate will ensure that when the player chooses a stream, the video will download faster than expected, and the buffer will fill up faster than expected, reducing the possibility of a stall. - CON

By overstating the bitrate, the video delivered will be a lower quality stream. If we look at the entire list of reported vs. actual bitrates:

| Reported (KBS) | Actual | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| 913 | 600 | 640×360 |

| 142 | 64 | 320×180 |

| 297 | 180 | 512×288 |

| 506 | 320 | 512×288 |

| 689 | 450 | 412×288 |

| 1410 | 950 | 853×480 |

| 2090 | 1500 | 1280×720 |

For users on a 1.6 MBPS connection, the player will choose the 913 KBPS bitrate, serving the customer 600 KBPS video. However, if the bitrates had been reported accurately, the 950 KBPS bitrate would be used, and would likely have streamed with no issues. While the choices here prevent stalls, they also lower the quality of the delivered video to the consumer.

Best Practice: A small overstatement of video bitrate may be useful to reduce the number of stalls in playback. However, too large a value can lead to reduced quality playback.

Test the Neilsen video in the browser, and see if you can make it jump back and forth.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve walked through a number of ways to optimize the videos that you present on your websites. By following the best practices illustrated in this post:

preload="auto"

Only use if there is a high probability that this video will be watched by your customers.preload="metadata"

Default in Chrome, but can still lead to large video file downloads. Use with caution.- Silent Videos (looping GIFs or background videos)

Strip out the audio channel - Video Dimensions

Consider delivering differently sized video to mobile over desktop. The videos will be smaller, download faster, and your users are unlikely to see the difference (your server load will go down too!) - Video Compression

Don’t forget to compress the videos to ensure that they are delivered - Don’t ‘hide’ videos

If the video will not be displayed — don’t download it. - Audit your third-party videos regularly

- Streaming

Start with a lower quality stream to ensure fast startup. (For longer play videos, consider a medium bitrate for better quality at startup) - Streaming

It’s OK to be conservative on bitrate to prevent stalling, but go too far, and the streams will deliver a lower quality video.

You will find that the video on your page is streamlined for optimal delivery and that your customers will not only delight in the video you present but also enjoy a faster page load time overall.

(dm, ra, il)

(dm, ra, il)

Articles on Smashing Magazine — For Web Designers And Developers