How Improving Website Performance Can Help Save The Planet

How Improving Website Performance Can Help Save The Planet

Jack Lenox

You may not think about it often, but the Internet uses a colossal amount of electricity. This electricity needs to be produced somewhere. In most countries, this means the burning of fossil fuels. This, in turn, means that the Internet’s carbon footprint has grown to the point where it may have eclipsed global air travel, and this makes the Internet the largest coal-fired machine on Earth.

The Mozilla Internet Health Report 2018 states that — especially as the Internet expands into new territory — “sustainability should be a bigger priority.” But as it stands, websites are growing ever more obese, which means that the energy demand of the Internet is continuing to grow exponentially.

All the while, the impacts of climate change grow worse and more numerous with each passing year. The vast majority of climate scientists attribute the increasing ferocity and frequency of extreme weather events around the world to climate change, which they largely attribute to human activity. While some question the science, even the world’s largest oil companies now accept it, and concede that their business models need to change.

Every country on Earth (with the exception of the US), is signed up to the Paris Climate Agreement. Although the US controversially pulled out, many of America’s most influential individuals, cities, states, and companies — representing more than half the US population and economy — have retained their commitment to the agreement by way of the America’s Pledge initiative.

As web developers, it’s understandable to feel that this is not an issue over which we have any influence, but this isn’t true. Many efforts are afoot to improve the situation on the web. The Green Web Foundation maintains an ever-growing database of web hosts who are either wholly powered by renewable energy or are at least committed to being carbon neutral. In 2013, A List Apart published Sustainable Web Design by James Christie. For the last three years, the SustainableUX conference has seen experts in web sustainability sharing their knowledge across an array of web-based disciplines.

Since 2009, Greenpeace has been putting pressure on big Internet companies to clean up their energy mix by way of their Clicking Clean campaign. Partly as a result of this campaign, Google announced last year that for the first time it had purchased enough renewable energy to match 100% of its global consumption for operations.

So, apart from powering servers with renewable energy, what else can web developers do about climate change?

“You Can’t Manage What You Can’t Measure”

Perhaps the biggest win when it comes to making websites more sustainable is that performance, user experience and sustainability are all neatly intertwined. The key metric for measuring the sustainability of a digital product is its energy usage. This includes the work done by the server, the client and the intermediary communications networks that transmit data between the two.

With that in mind, perhaps the first thing to consider is how do we measure the energy usage of our website? This is actually a trickier undertaking than you might imagine, and it’s difficult to get precise data here. There are, however, some good fallbacks which we can use that demonstrate energy usage. These include data transfer (i.e. how much data does the browser have to download to display your website) and resource usage of the hardware serving and receiving the website. An obvious metric here is CPU usage, but memory usage and other forms of data storage also play their part.

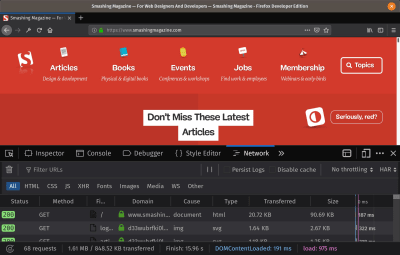

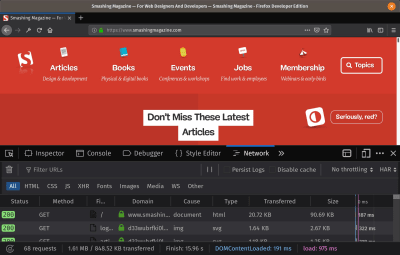

Data transfer is one thing that we can measure quite easily. All of the major browsers provide developer tools that allow us to measure network activity. In this screenshot below, for example, we can see that loading the Smashing Magazine website for the first time incurs just under a megabyte of data transfer. Firefox’s developer tools actually provide us with two numbers: the first is the uncompressed size of the files that have been transferred, and the latter is the compressed size.

The most common tool for compressing assets as they travel across the network is gzip, so the difference between those two numbers is typically a result of gzip’s work. This latter number represents how much data has actually been transmitted and is the one to keep an eye on.

Note: There are plenty of other tools that provide us with a metric for data transfer including the much revered WebPagetest.

For measuring CPU usage, Chrome provides us with a granular Task Manager that shows the memory footprint, CPU usage and network activity of individual tabs. For the more adventurous/technical, the top (table of processes) command provides similar metrics on most Unix-like operating systems such as macOS and Ubuntu. Generally speaking, we can also run the top command on any server to which we have shell access.

Fortunately, there are efforts such as WebsiteCarbon and Ecograder that seek to translate these metrics into a specific CO2 figure (in the case of WebsiteCarbon) or a score (in the case of Ecograder).

Sustainable Web Design

Now we know how to measure the impact of our site, it’s time to think about how we can optimize things to make it more sustainable, more performant, and generally a better experience to use.

There are some existing works we can draw on to help us here. In 2016, O’Reilly published “Designing For Sustainability” by Tim Frick. In this book, Tim takes us on a tour of the whys and hows of sustainable design. But we can also draw on a wealth of existing ideas, conference talks and articles which — while not having an explicit focus on sustainability — have a huge overlap with the philosophy of sustainable web design. Particularly good examples here are Brad Frost’s side-project, “Death To Bullshit”, Heydon Pickering’s articles and talks about writing less damn code, and Adam Silver’s blog post, “Designing For Actual Performance.”

If we’re doing a complete redesign of a website, or starting a new one from scratch, we can start with some really high-level questions here. For example, what actually deserves or needs to be on a homepage? And more specifically, what value does each element on a homepage bring? As Heydon Pickering puts it:

“The most performant, accessible and easily maintainable feature of a website is the one that you don’t make in the first place.”

I work on the WordPress.com VIP team, so in this vein, I decided to challenge myself by putting together a minimalist WordPress theme to see how far I could take the techniques of sustainable web design. The result is a theme called Susty, and it can be seen in action on the accompanying website I put together: sustywp.com. In that particular example, the website is delivered in just over 6KB of data transfer, which feels good given that the median website is about 1.5MB.

So, what did I do? Well, I’ll tell you.

Reduce Network Requests

As I have outlined above, network requests are something we can easily measure, so they make for a good starting point. In putting Susty together, I noticed there were a number of HTTP requests going on that didn’t appear to be necessary. For example, WordPress bundles some CSS and JavaScript that detects the usage of emojis and makes sure they don’t appear as illegal characters. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this, but if you aren’t planning to use emojis, or you’re happy and confident that the various system defaults will have you covered, you can prevent these from loading.

This represents a relatively meager saving, but by establishing a philosophy of pruning unwanted code and requests from our pages, we can make much more significant performance improvements. For example:

- Are we loading the whole of jQuery for some basic DOM operations?

Could we achieve the same ends with pure JavaScript? You can read about more advanced dead code elimination (aka tree shaking) in this post for Google by Jeremy Wagner. - Do we have a carousel of images?

Do we really need all those images? Are they significantly enhancing the user experience? Or could we reduce it to just one, strong image? Or even randomly show one of a selection of images, to give a sense of dynamism to returning users? By the way, the research that has been done here shows that most users neither like nor engage with carousels. - If we are using a lot of images, would we benefit from providing our images using the WebP format for those browsers that support it?

For the longest time, WebP’s support has been frustratingly limited. But with Firefox due to begin support for it in version 65 (due in January 2019), it’s only a matter of time before remaining stragglers like Safari catch up. - Are we loading hundreds of kilobytes of web fonts?

Are we using all of the web fonts that we’re loading? Do we even need web fonts? Most devices these days have a stack of half-decent fonts, could we just specify a list of fonts we’d like to see arranged by preference? If we must use web fonts, we should make sure our fonts are as performant as is reasonably possible. - Are we embedding YouTube videos?

An embedded YouTube video typically adds about a megabyte of data transfer before anyone even interacts with it. If only a fraction of our users are actually going to sit and watch the embedded video on our website, could we just link to it instead?

Scrutinise Everything

In this vein, we can also interrogate every aspect of our pages. What really deserves to be there? Does our sidebar add any real value, or have we just put one there because convention dictates that websites have sidebars? So, we’ve added one and filled it with crap.

With Susty, I’ve experimented with the somewhat unorthodox approach of relegating the navigation to its own page. This allows me to have pages that are stripped down to literally the bare essentials, with additional content only being loaded at the user’s explicit request. Susty is so lightweight and so fast that I realized through some user research (aka my partner) that the loading of the menu didn’t really feel like a new page, so I decided to make it look like an overlay, with a cross to dismiss that actually just takes you back to the previous page.

As well as helping me to create pleasingly lightweight pages, the relegated navigation also removes the need for any fancy hide/reveal code for showing it. At this point, I’d like to make it clear that Susty is an example of taking sustainable web design techniques to an extreme (I’m not suggesting it’s an archetype of a good website).

Write CSS Like Your Grandmother

When it comes to serious performance enhancement, we should bear in mind that literally every character of code counts. Every character represents a byte, and even after they’ve been compressed by gzip, they’re still taking up weight. CSS is a domain where we often see a lot of bloat. Fortunately, there are a growing number of increasingly complex tools that can help you weed out unused CSS. This fantastic post by Sarah Dayan outlines how she reduced her CSS bundle from 259KB to 9KB!

If we’re starting from scratch, perhaps we should think more deeply about how we write CSS in the first place. Heydon Pickering wrote an excellent post about how we can write CSS in a way that plays to the strengths of how the syntax was designed, and how this can help developers prevent repetition. Heydon also points out how much wastage goes on with excessive usage of divs and classes — both in HTML and CSS.

What Are You Analyzing?

It seems to have become more-or-less ubiquitous on the web for everyone to analyze what their website’s visitors do via tools like Google Analytics, KISSmetrics, Piwik, etc. While I have no doubt that there are legitimate use cases, do we really need analytics on every website? I, for one, have typically added Google Analytics to every site I manage as a matter of course. But it dawned on me relatively recently that for most of the websites in question, this has been an almost completely pointless endeavor: “Oh, six people came to this post via Facebook today.” Who cares?

Unless you really need it, and you’re going to analyze and act upon the data, just ditch analytics and find a better way to spend your time than gawping at the mundanity of how many people visited website X today.

As well as adding to your page weight, usage of something like Google Analytics raises ethical questions around the data you’re collecting on your users on Google’s behalf, i.e. there’s a reason Google provides you with Analytics for free.

Let’s Not Forget The Basics

There’s so much information around these days about the following, but we should never get complacent and forget about them. Alongside everything above, we absolutely should always minify HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and concatenate where appropriate. We should also compress all images to ensure they are as small as possible, use the right formats in the right settings, and use progressive rendering.

Server-Side Performance

So far, our focus has been almost entirely on the front-end, but a lot of this is made irrelevant if we don’t also optimize things on the server-side. I’ve already mentioned it a couple of times, but we should absolutely enable gzip compression at all times.

We should make serving our website as easy for our server as possible. I predominantly use Nginx, and I have a particular fondness for FastCGI cache and have found it to be especially efficient. If you have shell access to your own server, here’s a post that explains how to configure it. There are less technical options if you don’t have (or don’t want) as much control over your server. A particular favorite in the WordPress space is WP Super Cache.

We should use HTTP2 over HTTPS. Using HTTPS opens up a world of new web technologies like service workers that allow us to treat the network itself as a nice-to-have. If you want to learn more about this, I highly recommend Jeremy Keith’s new book, “Going Offline.”

Note: You also may want to investigate Google’s PageSpeed Module, available for both Apache and Nginx.

Finally, the biggest impact we can have here is to host our websites in data centers powered by renewable energy. In the UK, I can highly recommend Krystal and Kualo in terms of companies with which I directly host my sites. (For a full directory of green web hosts, check out The Green Web Foundation.)

In Conclusion

I hope I have convinced you that it’s worth putting in the effort to make our websites more sustainable. Especially given that in the process we also make our websites:

- More performant,

- More user-friendly,

- More accessible,

- More server-friendly,

- Better optimized for search engines.

A response that some people have to the idea of sustainable web design — which is not unreasonable — is that it seems to be a very small concession to the environmental cause. Of course, how much of an impact you can have depends on how busy the websites are that you work on. But as well as helping the web become a bit more environmentally friendly, sustainable web design is fundamentally best practice web design.

It’s also worth thinking about offsetting the carbon emissions that you can’t avoid. Carbon offsetting is sometimes derided, and with good cause. The main problem with offsetting is that typically the term over which carbon will be offset is quite long. For example, with tree planting, the figure given for an amount of carbon sequestering is typically based over a 100-year period. So, in terms of reducing carbon emissions now, it’s not really a solution. But it is better than nothing.

The motto of myclimate is to do your best, and offset the rest. I have written a blog post about rolling your own carbon offset scheme. I also highly recommend the 1% For The Planet initiative. Finally, if you are a business owner and would like to join an alliance of companies that want to see better social, environmental and economic justice, check out the Certified B Corporation scheme.

(ra, il)

(ra, il)

Articles on Smashing Magazine — For Web Designers And Developers