Avoid Keyboard Event-Related Bugs In Browser-Based Transliteration

Avoid Keyboard Event-Related Bugs In Browser-Based Transliteration

Sandamal Siripathi

Google’s multi-language input method, known as Google Input Tools is a good example of a web app that uses transliteration to input non-English characters. The basic idea is to have a text box, in which users spell the words of their own language, using English characters. They usually type those words using an English keyboard. The web app converts the typed English keystrokes into characters of their local (non-English) language, and displays those non-English characters in the text box in real-time. Users can copy the text from the text box and paste it into whatever the text field or search bar on another web page or app.

In this article, we’ll see how Google Input Tools behaves on a desktop and a mobile browser and identify its weakness, when running on the Chrome browser on Android. We’ll also compare that with the performance of our alternative JavaScript code snippet, and appreciate how it avoids the issues related to the Chrome mobile browser. You can use this method when you develop your own alternative to Google Input Tools in the future.

Using The Web With Just A Keyboard

Many of us are taught to make sure our sites can be used via keyboard. Why is that, and what is it like in practice? Chris Ashton did an experiment to find out. Read a related article →

Google Input Tools

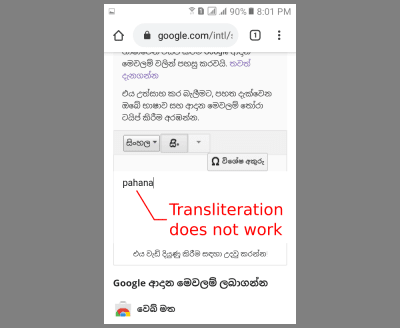

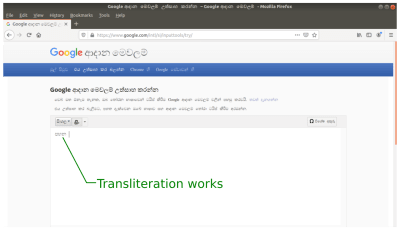

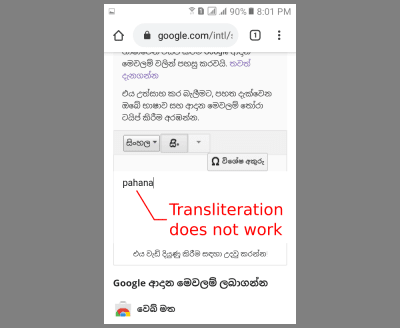

Below you can see how Google Input Tools works on a desktop and a mobile browser. It is obvious that transliteration doesn’t work on Chrome mobile browser (on Android) due to some kind of a bug. You can check for yourself by visiting Google Input Tools on a PC and a mobile device running Android with Chrome browser.

We’ll try it out by typing a very simple word in Sinhala, an official language of the South Asian island, Sri Lanka. We’ll type the Sinhala word “පහන”, meaning “lamp” in English. The mapping specified by Google Input Tools is “pa” for “ප”, “ha” for “හ” and “na” for “න”. So, just type “pahana” in the Google Input Tools text box and hit Enter. The mapped Sinhala characters, “පහන” will appear in the textbox.

Try this on a desktop and an Android mobile device with the Chrome browser. As seen in the images below, it works on the Firefox desktop browser but fails on the Chrome mobile browser.

How did it happen? It works perfectly on a desktop browser, but fails on the Chrome mobile browser running on Android.

Two Possible Methods

Conversion of keystrokes can easily be implemented using JavaScript. If word prediction is also involved, then there’s a need for a back-end database and hence PHP, but the basic functionality can be achieved only with JavaScript.

Two methods could be used to implement this. Here, we’ll limit our example to a very simple input method design, where each non-English character can directly be mapped to a unique single keystroke.

For example, we could map the non-English (Sinhala) character “ප” to the English character “p”, or the key “p” on the keyboard.

- Method 1 (Typical Method):

Prevent Default Behavior and Capture Keyboard EventThere are two main steps to achieve this with JavaScript in method 1. First, the default behavior when a key is pressed or held down must be stopped. Then the desired character or characters to be typed must be specified in the KeyPress, KeyDown or KeyUp event capture functions.

The default behavior when a key is pressed or held down, is to type the character associated with that key on the keyboard. For example, when the key “p” is pressed, the English character “p” will be typed in the text box by default. We could prevent this default behavior and replace the default character for any key, with a non-English character of our choice.

In our example, we’ll prevent typing of “p” when the key “p” is pressed and programmatically insert the mapped character “ප” instead of character “p”. We can do this for all the mapped characters on the keyboard. - Method 2 (New Method):

Listen to the Textbox Input and Modify the Contents in Real-Time, Based on Latest InputIn this method, we are not dealing with any keyboard events. Instead, we’ll keep track of the latest input character in the textbox and replace that character with a non-English character of our choice.

In the background, our script must be listening to the changes in the contents of the textbox. When the key “p” is pressed let “p” be typed. When the script detects that the last typed character is “p”, it must programmatically delete that typed “p” and replace it with “ප”. In a similar fashion, any non-English character can be typed by assigning them to an English character through an appropriate mapping.

Whenever an English character is typed by pressing a key on the keyboard, all you have to do is to programmatically delete that typed character and replace it with the non-English character specified in the mapping.

Which Method Does Google Input Tools Use?

From what’s happening in the two different scenarios, it seems that Google Input Tools is using the first method (Method 1), which is also the typical way of implementing such functionality. Now that we’ve invented a new method (Method 2), it’s time for a little bit of experimentation.

Let’s Compare the Two Methods

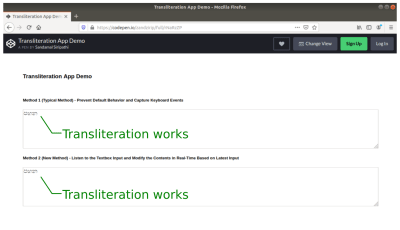

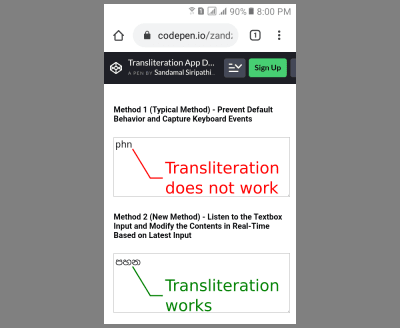

Below you can compare how the two different methods perform on Firefox on a laptop and Chrome mobile browser on an Android mobile device. Unlike Google Input Tools, which uses more than one English character per non-English character, we have already used a one-to-one mapping for simplicity. According to our mapping, “p” equals “ප”, “h” equals “හ”, and “n” equals “න”. So, just type “phn” to produce the Sinhala word “පහන”.

Only Method 2 (that’s our new method) can handle both laptop and Chrome mobile browser without any problem. Method 1 (the typical method) fails when it comes to the Chrome mobile browser.

You can also visit my CodePen and verify by yourself.

Fix Another Minor Issue

If you experience some unexpected results when you type using transliteration on your Android mobile, that’s because you have enabled text prediction on your mobile’s soft keyboard. Just disable text prediction, auto suggestions plus auto-capitalization and it should work like magic.

However, SwiftKey (pre-installed on most Huawei phones) doesn’t allow the word prediction to be disabled. So, installing an alternative such as a Gboard keyboard will fix that problem. Disable text prediction plus auto-suggestions and start typing.

This following CodePen example provides you with the complete source code:

See the Pen [Transliteration App Demo](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/eYNGzqW]) by Sandamal Siripathi.

Code Review

To demonstrate Method 1 and Method 2, I created two text areas named textarea1 and textarea2 in a normal HTML file. Then I added some CSS styling to make them look nice on the web page. Using two JavaScript scripts to change the contents of those two textboxes, I was able to implement the two methods, which I wanted to experiment with.

For Method 1

I devised a method to capture the keydown event and call a function named “whichKey” when the keydown event fires. JavaScript onkeydown event fires whenever a user presses a key on the keyboard. I used that to capture the keyboard event.

Function whichKey handles the core job of preventing default behavior when a key is pressed. It then calls another function named “typeIt1”, which is responsible for typing the actual non-English (Sinhala) characters according to the mapping of our choice. Whenever a key is pressed on the keyboard, the function whichKey passes that pressed key to the function typeIt1, which in turn types the relevant Sinhala character in the text box.

You can refer to the well-commented example on CodePen and see for yourself how that has been achieved:

See the Pen [Transliteration App Demo](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/rNVGMNw]) by Sandamal Siripathi.

For Method 2

Since the bug on Chrome browser on Android, fails to perform the transliteration correctly, it still displays the English characters instead of converting them to Sinhala characters. Yet, it works fine on a desktop browser. So, I suspected the bug was caused by not correctly capturing the keyboard events on the Chrome browser running on Android.

Since fixing the browser bug was clearly beyond my capabilities, I decided to go for a clever trick. What if I could avoid the bug, rather than trying to fix it? With a little more innovative thinking, I was able to come up with a solution.

I switched to a completely new method that doesn’t rely on keyboard event capturing. My idea was to keep track of the changes in the contents of the textbox. When a key is pressed, the contents of this textbox will naturally change. Based on that change, it’s always possible to introduce another change, using JavaScript.

For example, start with an empty textbox. Now, suppose the key “p” was pressed. Then the textbox’s contents will change from blank to “p”. The script running in the background will detect this change and replace “p” with a non-English character of my choice. This choice could be based on some predetermined mapping between English characters on the keyboard and non-English characters of the language, in which we want to type.

To demonstrate this, I added an oninput event to textarea2. I specifically selected oninput instead of onchange, because the latter updates the contents only after the textbox loses focus, while the former updates it immediately on pressing the keys. When the oninput event fires, it will call a function named “typeIt2”, which handles the process of replacing the typed English character with the relevant non-English character.

Again, there’s another example on CodePen that describes all of the necessary information you need to understand how this has been implemented.

See the Pen [Transliteration App Demo](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/rNVGMaz]) by Sandamal Siripathi.

Conclusion

It’s obvious that our new method can successfully avoid the transliteration-related problem on the Chrome browser running on Android. Although we used a one-to-one mapping between English and non-English characters for the sake of simplicity, such a simple mapping might not be always possible. Most of these languages — especially the Asian ones — are full of very complex features and may require more advanced mappings. Sinhala language, for example, has independent vowels, consonants, dependent vowel signs, additional dependent vowel signs, punctuation and various other signs.

Note: For more details about Sinhala Unicode code charts, you can visit the relevant page on The Unicode Consortium. If you are thinking of developing text input apps for non-English languages, I recommend you visit The Unicode Consortium and improve your knowledge about Unicode before actually starting your project. It provides you with full coverage of the subject including the basics, best practices, and in-depth technical details.

If you ever wanted to develop an alternative to Google Input Tools, now you are in a better position to do that.

(dm, il)

(dm, il)

Articles on Smashing Magazine — For Web Designers And Developers