A Strategy Guide To CSS Custom Properties

A Strategy Guide To CSS Custom Properties

Michael Riethmuller

CSS Custom Properties (sometimes known as ‘CSS variables’) are now supported in all modern browsers, and people are starting to use them in production. This is great, but they’re different from variables in preprocessors, and I’ve already seen many examples of people using them without considering what advantages they offer.

Custom properties have a huge potential to change how we write and structure CSS and to a lesser extent, how we use JavaScript to interact with UI components. I’m not going to focus on the syntax and how they work (for that I recommend you read “It’s Time To Start Using Custom Properties”). Instead, I want to take a deeper look at strategies for getting the most out of CSS Custom Properties.

How Are They Similar To Variables In Preprocessors?

Custom Properties are a little bit like variables in preprocessors but have some important differences. The first and most obvious difference is the syntax.

With SCSS we use a dollar symbol to denote a variable:

$ smashing-red: #d33a2c;In Less we use an @ symbol:

@smashing-red: #d33a2c;Custom properties follow a similar conventions and use a -- prefix:

:root { --smashing-red: #d33a2c; } .smashing-text { color: var(--smashing-red); } One important difference between custom properties and variables in preprocessors is that custom properties have a different syntax for assigning a value and retrieving that value. When retrieving the value of a custom property we use the var() function.

The next most obvious difference is in the name. They are called ‘custom properties’ because they really are CSS properties. In preprocessors, you can declare and use variables almost anywhere, including outside declaration blocks, in media rules, or even as part of a selector.

$ breakpoint: 800px; $ smashing-red: #d33a2c; $ smashing-things: ".smashing-text, .cats"; @media screen and (min-width: $ breakpoint) { #{$ smashing-things} { color: $ smashing-red; } } Most of the examples above would be invalid using custom properties.

Custom properties have the same rules about where they can be used as normal CSS properties. It’s far better to think of them as dynamic properties than variables. That means they can only be used inside a declaration block, or in other words, custom properties are tied to a selector. This can be the :root selector, or any other valid selector.

:root { --smashing-red: #d33a2c; } @media screen and (min-width: 800px) { .smashing-text, .cats { --margin-left: 1em; } } You can retrieve the value of a custom property anywhere you would otherwise use a value in a property declaration. This means they can be used as a single value, as part of a shorthand statement or even inside calc() equations.

.smashing-text, .cats { color: var(--smashing-red); margin: 0 var(--margin-horizontal); padding: calc(var(--margin-horizontal) / 2) } However, they cannot be used in media queries, or selectors including :nth-child().

There is probably a lot more you want to know about the syntax and how custom properties work, such as how to use fallback values and can you assign variables to other variables (yes), but this basic introduction should be enough to understand the rest of the concepts in this article. For more information on the specifics of how custom properties work, you can read “It’s Time To Start Using Custom Properties” written by Serg Hospodarets.

Dynamic vs. Static

Cosmetic differences aside, the most significant difference between variables in preprocessors and custom properties is how they are scoped. We can refer to variables as either statically or dynamically scoped. Variables in preprocessors are static, whereas custom properties are dynamic.

Where CSS is concerned, static means that you can update the value of a variable at different points in the compilation process, but this cannot change the value of the code that came before it.

$ background: blue; .blue { background: $ background; } $ background: red; .red { background: $ background; } results in:

.blue { background: blue; } .red { background: red; } Once this is rendered to CSS, the variables are gone. This means that we could potentially read an .scss file and determine its output without knowing anything about the HTML, browser or other inputs. This is not the case with custom properties.

Preprocessors do have a kind of “block scope” where variables can be temporarily changed inside a selector, function or mixin. This changes the value of a variable inside the block, but it’s still static. This is tied to the block, not the selector. In the example below, the variable $ background is changed inside the .example block. It changes back to the initial value outside the block, even if we use the same selector.

$ background: red; .example { $ background: blue; background: $ background; } .example { background: $ background; } This will result in:

.example { background: blue; } .example { background: red; } Custom properties work differently. Where custom properties are concerned, dynamically scoped means they are subject to inheritance and the cascade. The property is tied to a selector and if the value changes, this affects all matching DOM elements just like any other CSS property.

This is great because you can change the value of a custom property inside a media query, with a pseudo selector such as hover, or even with JavaScript.

a { --link-color: black; } a:hover, a:focus { --link-color: tomato; } @media screen and (min-width: 600px) { a { --link-color: blue; } } a { color: var(--link-color); } We don’t have to change where the custom property is used — we change the value of the custom property with CSS. This means using the same custom property, we can have different values in different places or context on the same page.

Global vs. Local

In addition to being static or dynamic, variables can also be either global or local. If you write JavaScript, you will be familiar with this. Variables can either be applied to everything inside an application, or their scope can be limited to specific functions or blocks of code.

CSS is similar. We have some things that are applied globally and some things that are more local. Brand colors, vertical spacing, and typography are all examples of things you might want to be applied globally and consistently across your website or application. We also have local things. For example, a button component might have a small and large variant. You wouldn’t want the sizes from these buttons to be applied to all input elements or even every element on the page.

This is something we are familiar with in CSS. We’ve developed design systems, naming conventions and JavaScript libraries, all to help with isolating local components and global design elements. Custom properties provide new options for dealing with this old problem.

CSS Custom Properties are by default locally scoped to the specific selectors we apply them to. So they are kinda like local variables. However, custom properties are also inherited, so in many situations they behave like global variables — especially when applied to the :root selector. This means that we need to be thoughtful about how to use them.

So many examples show custom properties being applied to the :root element and although, this is fine for a demo, it can result in a messy global scope and unintended issues with inheritance. Luckily, we’ve already learned these lessons.

Global Variables Tend To Be Static

There are a few small exceptions, but generally speaking, most global things in CSS are also static.

Global variables like brand colors, typography and spacing don’t tend to change much from one component to the next. When they do change, this tends to be a global rebranding or some other significant change that rarely happens on a mature product. It still makes sense for these things to be variables, they are used in many places, and variables help with consistency. But it doesn’t make sense for them to be dynamic. The value of these variables does not change in any dynamic way.

For this reason, I strongly recommend using preprocessors for global (static) variables. This not only ensures that they are always static, but it visually denotes them within the code. This can make CSS a whole lot more readable and easier to maintain.

Local Static Variables Are OK (Sometimes)

You might think given the strong stance on global variables being static, that by reflection, all local variables might need to be dynamic. While it’s true that local variables do tend to be dynamic, this is nowhere near as strong as the tendency for a global variable to be static.

Locally static variables are perfectly OK in many situations. I use preprocessors variables in component files mostly as a developer convenience.

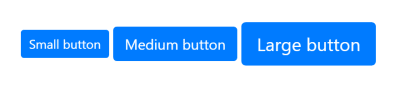

Consider the classic example of a button component with multiple size variations.

My scss might look something like this:

$ button-sml: 1em; $ button-med: 1.5em; $ button-lrg: 2em; .btn { // Visual styles } .btn-sml { font-size: $ button-sml; } .btn-med { font-size: $ button-med; } .btn-lrg { font-size: $ button-lrg; } Obviously, this example would make more sense if I was using the variables multiple times or deriving margin and padding values from the size variables. However, the ability to quickly prototype different sizes might be a sufficient reason.

Because most static variables are global, I like to differentiate static variables that are used only inside a component. To do this, you can prefix these variables with the component name, or you could use another prefix such as c-variable-name for component or l-variable-name for local. You can use whatever prefix you want, or you can prefix global variables. Whatever you choose, it’s helpful to differentiate especially if converting an existing codebase to use custom properties.

When To Use Custom Properties

If it is alright to use static variables inside components, when should we use custom properties? Converting existing preprocessor variables to custom properties usually makes little sense. After all, the reason for custom properties is completely different. Custom properties make sense when we have CSS properties that change relative to a condition in the DOM — especially a dynamic condition such as :focus, :hover, media queries or with JavaScript.

I suspect we will always use some form of static variables, although we might need fewer in future, as custom properties offer new ways to organise logic and code. Until then, I think in most situations we are going to be working with a combination of preprocessor variables and custom properties.

It’s helpful to know that we can assign static variables to custom properties. Whether they are global or local, it makes sense in many situations to convert static variables, to locally dynamic custom properties.

Note: Did you know that $ var is valid value for a custom property? Recent versions of Sass recognize this, and therefore we need to interpolate variables assigned to custom properties, like this: #{$ var}. This tells Sass you want to output the value of the variable, rather than just $ var in the stylesheet. This is only needed for situations like custom properties, where variable names can also be a valid CSS.

If we take the button example above and decide all buttons should use the small variation on mobile devices, regardless of the class applied in the HTML, this is now a more dynamic situation. For this, we should use custom properties.

$ button-sml: 1em; $ button-med: 1.5em; $ button-lrg: 2em; .btn { --button-size: #{$ button-sml}; } @media screen and (min-width: 600px) { .btn-med { --button-size: #{$ button-med}; } .btn-lrg { --button-size: #{$ button-lrg}; } } .btn { font-size: var(--button-size); } Here I create a single custom property: --button-size. This custom property is initially scoped to all button elements using the btn class. I then change the value of --button-size above 600px for the classes btn-med and btn-lrg. Finally, I apply this custom property to all button elements in one place.

Don’t Be Too Clever

The dynamic nature of custom properties allows us to create some clever and complicated components.

With the introduction of preprocessors, many of us created libraries with clever abstractions using mixins and custom functions. In limited cases, examples like this are still useful today, but for the most part, the longer I work with preprocessors the fewer features I use. Today, I use preprocessors almost exclusively for static variables.

Custom properties will not (and should not) be immune from this type of experimentation, and I look forward to seeing many clever examples. But in the long run, readable and maintainable code will always win over clever abstractions (at least in production).

I read an excellent article on this topic on the Free Code Camp Medium recently. It was written by Bill Sourour and is called “Don’t Do It At Runtime. Do It At Design Time.” Rather than paraphrasing his arguments, I’ll let you read it.

One key difference between preprocessor variables and custom properties is that custom properties work at runtime. This means things that might have been borderline acceptable, in terms of complexity, with preprocessors might not be a good idea with custom properties.

One example that illustrated this for me recently was this:

:root { --font-scale: 1.2; --font-size-1: calc(var(--font-scale) * var(--font-size-2)); --font-size-2: calc(var(--font-scale) * var(--font-size-3)); --font-size-3: calc(var(--font-scale) * var(--font-size-4)); --font-size-4: 1rem; } This generates a modular scale. A modular scale is a series of numbers that relate to each other using a ratio. They are often used in web design and development to set font-sizes or spacing.

In this example, each custom property is determined using calc(), by taking the value of the previous custom property and multiplying this by the ratio. Doing this, we can get the next number in the scale.

This means the ratios are calculated at run-time and you can change them by updating only the value of the --font-scale property. For example:

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) { :root { --font-scale: 1.33; } } This is clever, concise and much quicker than calculating all the values again should you want to change the scale. It’s also something I would not do in production code.

Although the above example is useful for prototyping, in production, I’d much prefer to see something like this:

:root { --font-size-1: 1.728rem; --font-size-2: 1.44rem; --font-size-3: 1.2em; --font-size-4: 1em; } @media screen and (min-width: 800px) { :root { --font-size-1: 2.369rem; --font-size-2: 1.777rem; --font-size-3: 1.333rem; --font-size-4: 1rem; } } Similar to the example in Bill’s article, I find it helpful to see what the actual values are. We read code many more times than we write it and global values such as font scales change infrequently in production.

The above example is still not perfect. It violates the rule from earlier that global values should be static. I’d much prefer to use preprocessor variables and convert them to locally dynamic custom properties using the techniques demonstrated earlier.

It is also important to avoid situations where we go from using one custom property to a different custom property. This can happen when we name properties like this.

Change The Value Not The Variable

Change the value not the variable is one of the most important strategies for using custom properties effectively.

As a general rule, you should never change which custom property is used for any single purpose. It’s easy to do because this is exactly how we do things with preprocessors, but it makes little sense with custom properties.

In this example, we have two custom properties that are used on an example component. I switch from using the value of --font-size-small to --font-size-large depending on the screen size.

:root { --font-size-small: 1.2em; --font-size-large: 2em; } .example { font-size: var(--font-size-small); } @media screen and (min-width: 800px) { .example { font-size: var(--font-size-large); } } A better way to do this would be to define a single custom property scoped to the component. Then using a media query, or any other selector, change its value.

.example { --example-font-size: 1.2em; } @media screen and (min-width: 800px) { .example { --example-font-size: 2em; } } Finally, in a single place, I use the value of this custom property:

.example { font-size: var(--example-font-size); } In this example and others before it, media queries have only been used to change the value of custom properties. You might also notice there is only one place where the var() statement is used, and regular CSS properties are updated.

This separation between variable declarations and property declarations is intentional. There are many reasons for this, but the benefits are most obvious when thinking about responsive design.

Responsive Design With Custom Properties

One of the difficulties with responsive design when it relies heavily on media queries is that the no matter how you organize your CSS, styles relating to a particular component become fragmented across the stylesheet.

It can be very difficult to know what CSS properties are going to change. Still, CSS Custom Properties can help us organize some of the logic related to responsive design and make working with media queries a lot easier.

If It Changes, It’s A Variable

Properties that change using media queries are inherently dynamic and custom properties provide the means to express dynamic values in CSS. This means that if you are using a media query to change any CSS property, you should place this value in a custom property.

You can then move this, along with all the media rules, hover states or any dynamic selectors that define how the value changes, to the top of the document.

Separate Logic From Design

When done correctly, separation of logic and design means that media queries are only used to change the value of custom properties. It means all the logic related to responsive design should be at the top of the document, and wherever we see a var() statement in our CSS, we immediately know that this property that changes. With traditional methods of writing CSS, there was no way of knowing this at a glance.

Many of us got very good at reading and interpreting CSS at a glance while tracking in our head which properties changed in different situations. I’m tired of this, and I don’t want to do this anymore! Custom properties now provide a link between logic and its implementation, so we don’t need to track this, and that is incredibly useful!

The Logic Fold

The idea of declaring variables at the top of a document or function is not a new idea. It’s something we do in most languages, and it’s now something we can do in CSS as well. Writing CSS in this way creates a clear visual distinction between CSS at the top of the document and below. I need a way to differentiate these sections when I talk about them and the idea of a “logic fold” is a metaphor I’ve started using.

Above the fold contains all preprocessor variables and custom properties. This includes all the different values a custom property can have. It should be easy to trace how a custom property changes.

CSS below the fold is straightforward and highly declarative and easy to read. It feels like CSS before media queries and other necessary complexities of modern CSS.

Take a look at a really simple example of a six column flexbox grid system:

.row { --row-display: block; } @media screen and (min-width: 600px) { .row { --row-display: flex; } } The --row-display custom property is initially set to block. Above 600px the display mode is set to flex.

Below the fold might look like this:

.row { display: var(--row-display); flex-direction: row; flex-wrap: nowrap; } .col-1, .col-2, .col-3, .col-4, .col-5, .col-6 { flex-grow: 0; flex-shrink: 0; } .col-1 { flex-basis: 16.66%; } .col-2 { flex-basis: 33.33%; } .col-3 { flex-basis: 50%; } .col-4 { flex-basis: 66.66%; } .col-5 { flex-basis: 83.33%; } .col-6 { flex-basis: 100%; } We immediately know --row-display is a value that changes. Initially, it will be block, so the flex values will be ignored.

This example is fairly simple, but if we expanded it to include a flexible width column that fills the remaining space, it’s likely flex-grow, flex-shrink and flex-basis values would need to be converted to custom properties. You can try this or take a look at a more detailed example here.

Custom Properties For Theming

I’ve mostly argued against using custom properties for global dynamic variables and hopefully implied that attaching custom properties to the :root selector is in many cases considered harmful. But every rule has an exception, and for custom properties, it’s theming.

Limited use of global custom properties can make theming a whole lot easier.

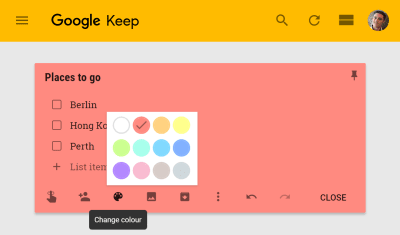

Theming generally refers to letting users customize the UI in some way. This could be something like changing colors on a profile page. Or it might be something more localized. For example, you can choose the color of a note in the Google Keep application.

Theming usually involves compiling a separate stylesheet to override a default value with user preferences, or compiling a different stylesheet for each user. Both of these can be difficult and have an impact on performance.

With custom properties, we don’t need to compile a different stylesheet; we only need to update the value of properties according to the user’s preferences. Since they are inherited values, if we do this on the root element they can be used anywhere in our application.

Capitalize Global Dynamic Properties

Custom properties are case sensitive and since most custom properties will be local, if you are using global dynamic properties, it can make sense to capitalize them.

:root { --THEME-COLOR: var(--user-theme-color, #d33a2c); } Capitalization of variables often signifies global constants. For us, this is going to signify that the property is set elsewhere in the application and that we should probably not change it locally.

Avoid Directly Setting Global Dynamic Properties

Custom properties accept a fallback value. It can be a useful to avoid directly overwriting the value of a global custom properties and keep user values separate. We can use the fallback value to do this.

The example above sets the value of --THEME-COLOR to the value of --user-theme-color if it exists. If --user-theme-color is not set, the value of #d33a2c will be used. This way, we don’t need to provide a fallback every time we use --THEME-COLOR.

You might expect in the example below that the background will be set to green. However, the value of --user-theme-color has not been set on the root element, so the value of --THEME-COLOR has not changed.

:root { --THEME-COLOR: var(--user-theme-color, #d33a2c); } body { --user-theme-color: green; background: var(--THEME-COLOR); } Indirectly setting global dynamic properties like this protects them from being overwritten locally and ensures user settings are always inherited from the root element. This is a useful convention to safeguard your theme values and avoid unintended inheritance.

If we do want to expose specific properties to inheritance, we can replace the :root selector with a * selector:

* { --THEME-COLOR: var(--user-theme-color, #d33a2c); } body { --user-theme-color: green; background: var(--THEME-COLOR); } Now the value of --THEME-COLOR is recalculated for every element and therefore the local value of --user-theme-color can be used. In other words, the background color in this example will be green.

You can see some more detailed examples of this pattern in the section on Manipulating Color With Custom Properties.

Updating Custom Properties With JavaScript

If you want to set custom properties using JavaScript there is a fairly simple API and it looks like this:

const elm = document.documentElement; elm.style.setProperty('--USER-THEME-COLOR', 'tomato'); Here I’m setting the value of --USER-THEME-COLOR on the document element, or in other words, the :root element where it will be inherited by all elements.

This is not a new API; it’s the same JavaScript method for updating styles on an element. These are inline styles so they will have a higher specificity than regular CSS.

This means it’s easy to apply local customizations:

.note { --note-color: #eaeaea; } .note { background: var(--note-color); } Here I set a default value for --note-color and scope this to the .note component. I keep the variable declaration separate from the property declaration, even in this simple example.

const elm = document.querySelector('#note-uid'); elm.style.setProperty('--note-color', 'yellow'); I then target a specific instance of a .note element and change the value of the --note-color custom property for that element only. This will now have higher specificity than the default value.

You can see how this works with this example using React. These user preferences could be saved in local storage or, perhaps in the case of a larger application, in a database.

Manipulating Color With Custom Properties

In addition to hex values and named colors, CSS has colors functions such as rgb() and hsl(). These allow us to specify individual components of a color such as the hue or lightness. Custom properties can be used in conjunction with color functions.

:root { --hue: 25; } body { background: hsl(var(--hue), 80%, 50%); } This is useful, but some of the most widely used features of preprocessors are advanced color functions that allow us to manipulate color using functions like lighten, darken or desaturate:

darken($ base-color, 10%); lighten($ base-color, 10%); desaturate($ base-color, 20%); It would be useful to have some of these features in browsers. They are coming, but until we have native color modification functions in CSS, custom properties could fill some of that gap.

We’ve seen that custom properties can be used inside existing color functions like rgb() and hsl() but they can also be used in calc(). This means that we can convert a real number to a percentage by multiplying it, e.g. calc(50 * 1%) = 50%.

:root { --lightness: 50; } body { background: hsl(25, 80%, calc(var(--lightness) * 1%)); } The reason we want to store the lightness value as a real number is so that we can manipulate it with calc before converting it to a percentage. For example, if I want to darken a color by 20%, I can multiply its lightness by 0.8. We can make this a little easier to read by separating the lightness calculation into a locally scoped custom property:

:root { --lightness: 50; } body { --lightness: calc(var(--lightness * 0.8)); background: hsl(25, 80%, calc(var(--lightness) * 1%)); } We could even abstract away more of the calculations and create something like color modification functions in CSS using custom properties. This example is likely too complex for most practical cases of theming, but it demonstrates the full power of dynamic custom properties.

Simplify Theming

One of the advantages of using custom properties is the ability to simplify theming. The application doesn’t need to be aware of how custom properties are used. Instead, we use JavaScript or server-side code to set the value of custom properties. How these values are used is determined by the stylesheets.

This means once again that we are able to separate logic from design. If you have a technical design team, authors can update stylesheets and decide how to apply custom properties without changing a single line of JavaScript or backend code.

Custom properties also allow as to move some of the complexity of theming into the CSS and this complexity can have a negative impact on the maintainability of your CSS, so remember to keep it simple wherever possible.

Using Custom Properties Today

Even if you’re supporting IE10 and 11, you can start using custom properties today. Most of the examples in this article have to do with how we write and structure CSS. The benefits are significant in terms of maintainability, however, most of the examples only reduce what could otherwise be done with more complex code.

I use a tool called postcss-css-variables to convert most of the features of custom properties into a static representation of the same code. Other similar tools ignore custom properties inside media queries or complex selectors, treating custom properties much like preprocessor variables.

What these tools cannot do is emulate the runtime features of custom properties. This means no dynamic features like theming or changing properties with JavaScript. This might be OK in many situations. Depending on the situation, UI customization might be considered a progressive enhancement and the default theme could be perfectly acceptable for older browsers.

Loading The Correct Stylesheet

There are many ways you can use postCSS. I use a gulp process to compile separate stylesheets for newer and older browsers. A simplified version of my gulp task looks like this:

import gulp from "gulp"; import sass from "gulp-sass"; import postcss from "gulp-postcss"; import rename from "gulp-rename"; import cssvariables from "postcss-css-variables"; import autoprefixer from "autoprefixer"; import cssnano from "cssnano"; gulp.task("css-no-vars", () => gulp .src("./src/css/*.scss") .pipe(sass().on("error", sass.logError)) .pipe(postcss([cssvariables(), cssnano()])) .pipe(rename({ extname: ".no-vars.css" })) .pipe(gulp.dest("./dist/css")) ); gulp.task("css", () => gulp .src("./src/css/*.scss") .pipe(sass().on("error", sass.logError)) .pipe(postcss([cssnano()])) .pipe(rename({ extname: ".css" })) .pipe(gulp.dest("./dist/css")) ); This results in two CSS files: a regular one with custom properties (styles.css) and one for older browsers (styles.no-vars.css). I want IE10 and 11 to be served styles.no-vars.css and other browsers to get the regular CSS file.

Normally, I’d advocate using feature queries but IE11 doesn’t support feature queries and we’ve used custom properties so extensively that serving a different stylesheet makes sense in this case.

Intelligently serving a different stylesheet and avoiding a flash of unstyled content is not a simple task. If you don’t need the dynamic features of custom properties, you could consider serving all browser styles.no-vars.css and using custom properties simply as a development tool.

If you want to take full advantage of all the dynamic features of custom properties, I suggest using a critical CSS technique. Following these techniques, the main stylesheet is loaded asynchronously while the critical CSS is rendered inline. Your page header might look something like this:

<head> <style> /* inlined critical CSS */ </style> <script> loadCSS('non-critical.css'); </script> </head> We can extend this to load either styles.css or styles.no-vars.css depending on whether the browser supports custom properties. We can detect support like this:

if ( window.CSS && CSS.supports('color', 'var(--test)') ) { loadCSS('styles.css'); } else { loadCSS('styles.no-vars.css'); } Conclusion

If you’ve been struggling to organize CSS efficiently, have difficulty with responsive components, want to implement client-side theming, or just want to start off on the right foot with custom properties, this guide should tell you everything you need to know.

It comes down to understanding the difference between dynamic and static variables in CSS as well as a few simple rules:

- Separate logic from design;

- If a CSS property changes, consider using a custom property;

- Change the value of custom properties, not which custom property is used;

- Global variables are usually static.

If you follow these conventions, you will find that working with custom properties is a whole lot easier than you think. This might even change how you approach CSS in general.

Further Reading

- “It’s Time To Start Using Custom Properties,” Serg Hospodarets

A general introduction to the syntax and the features of custom properties. - “Pragmatic, Practical, And Progressive Theming With Custom Properties,” Harry Roberts

More useful information on theming. - Custom Properties Collection, Mike Riethmuller on CodePen

A number of different examples you can experiment with.

(ra, yk, il)

(ra, yk, il)

Articles on Smashing Magazine — For Web Designers And Developers